Aussie Q4 CPI In-depth

Encouraging signs

Australia’s Q4 CPI inflation was below market expectations and the RBA’s November SMP forecasts. We were below consensus and the key underlying and ‘domestic’ inflation metrics printed in line with our expectations.

Next Tuesday’s RBA Board decision is an ‘on hold’ no-brainer. The Bank will publish updated forecasts in the overhauled Statement on Monetary Policy at the same time as the policy decision. We expect the new SMP format to be more concise and punchier than previously.

The Bank’s near-term underlying inflation forecasts are likely to be lowered a little, but we doubt the forecasts further out will change much.

It’s time, however, in our view for the Board to drop this language from the post-meeting statement and suggest that they have done enough:

“Whether further tightening of monetary policy is required to ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe will depend upon the data and the evolving assessment of risks.”

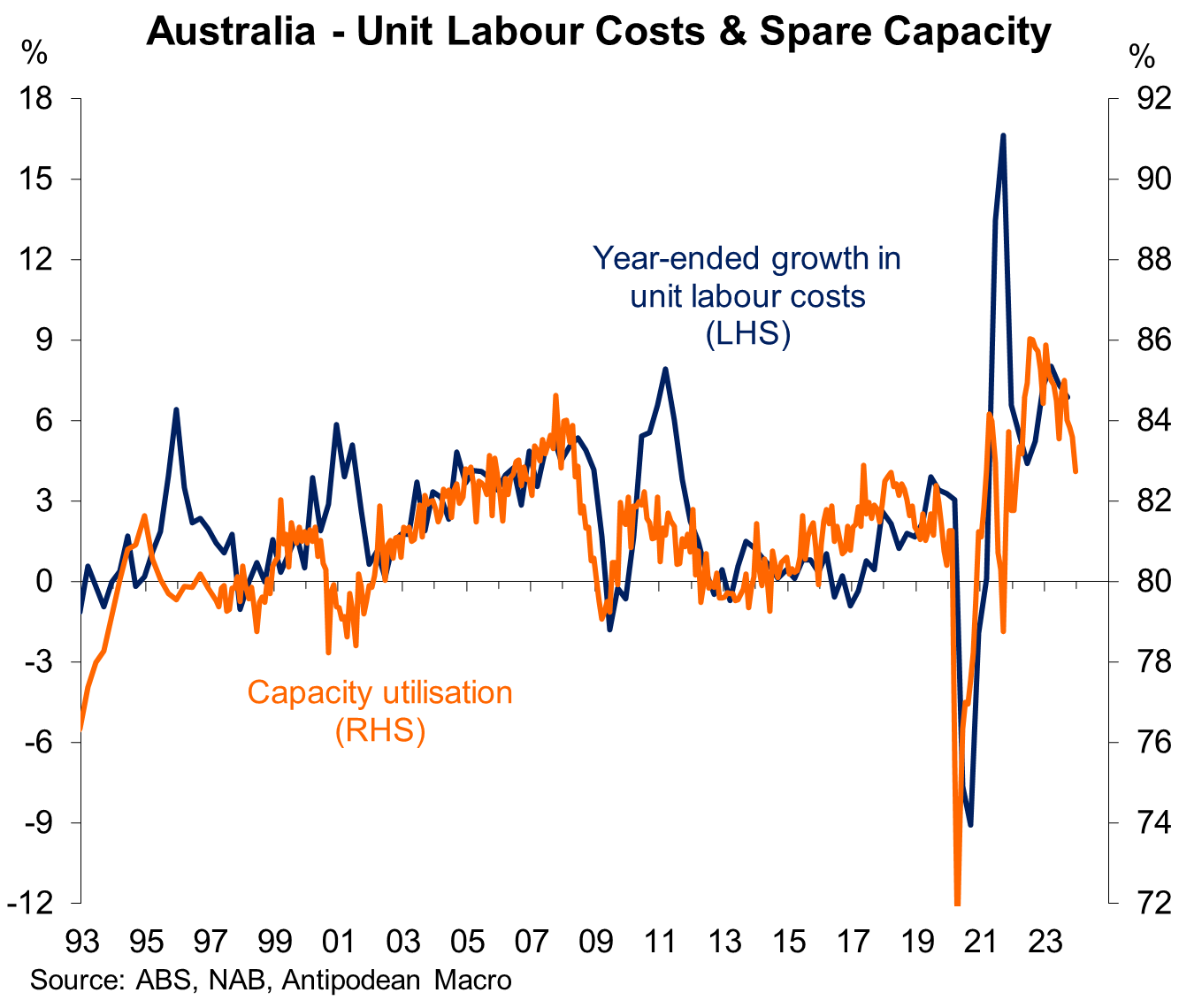

Our view is the RBA Board will keep the cash rate at 4.35% for a while now and until there are clearer signs of labour market deterioration. Labour market conditions continue to gradually ease but the level of spare capacity remains relatively modest.

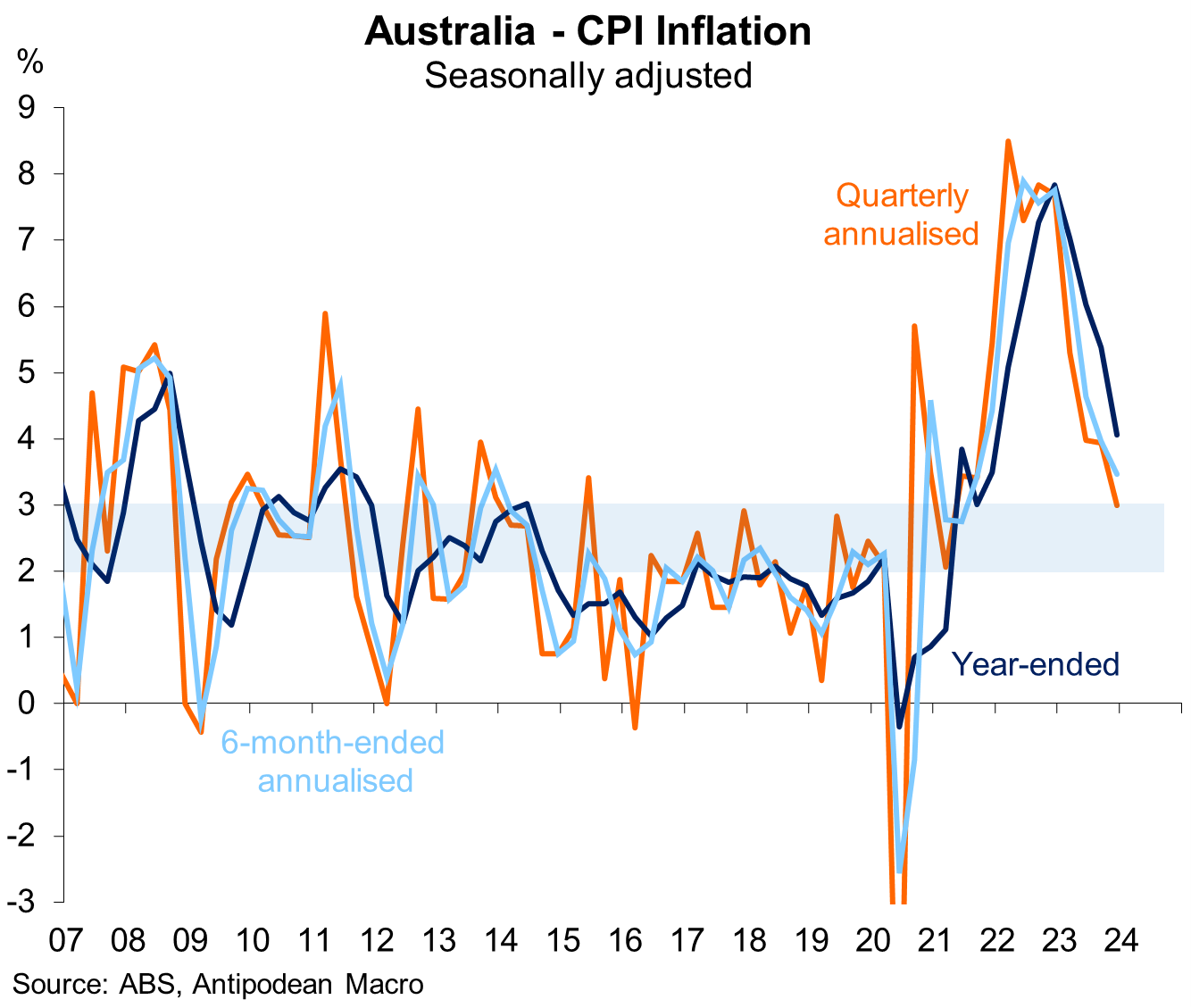

Inflation has fallen substantially

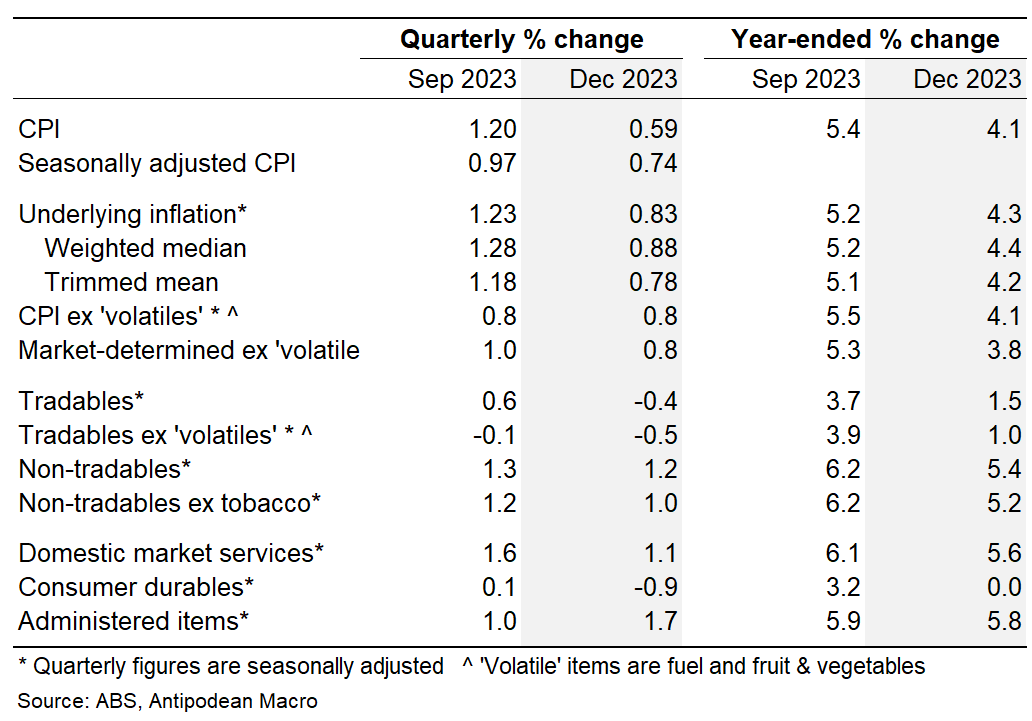

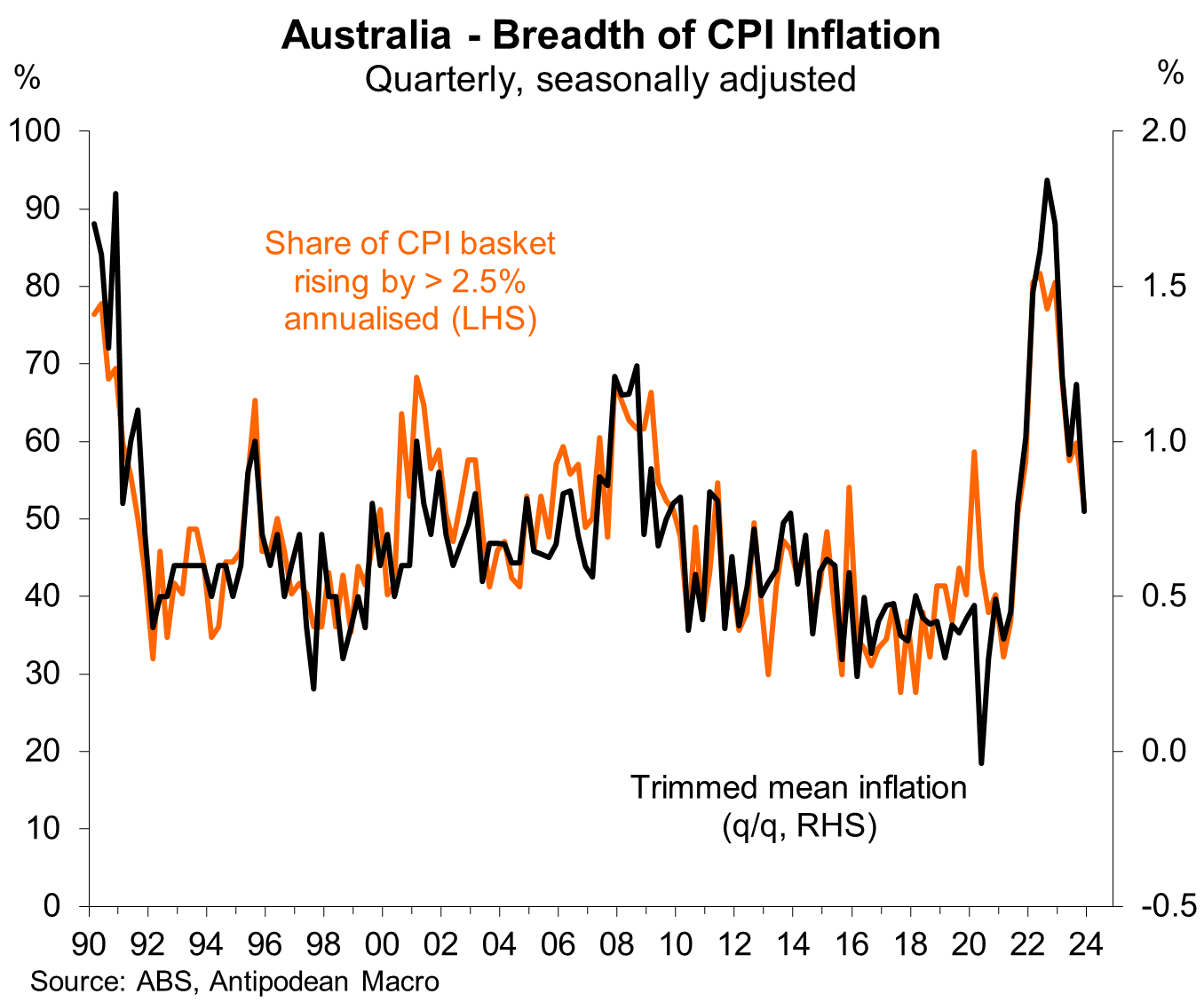

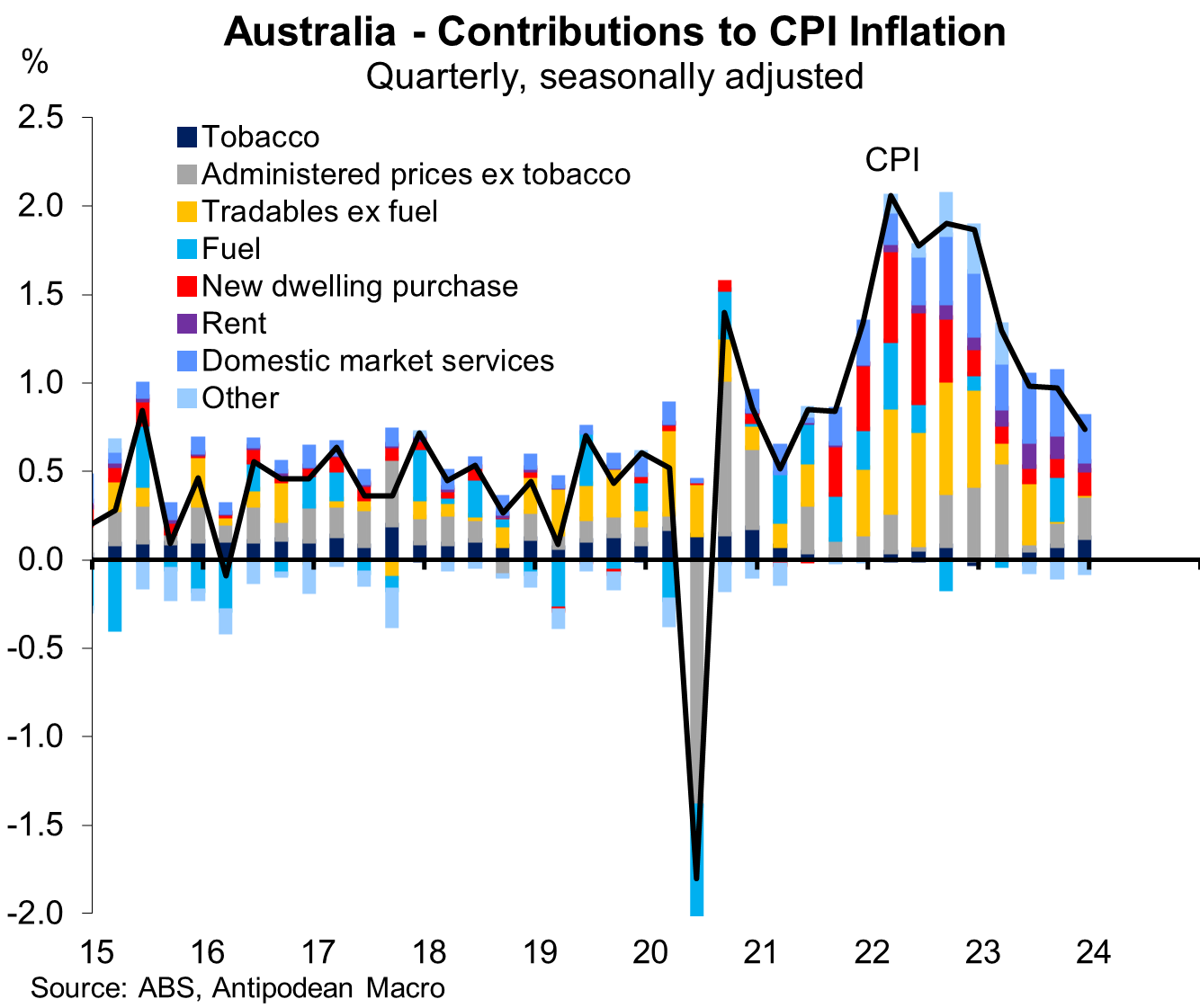

Annualised quarterly inflation fell to the top of the RBA’s 2-3% target in Q4 (using seasonally adjusted data). Volatile quarterly data mean that victory cannot be declared, but the degree of disinflation in Australia has so far been significant.

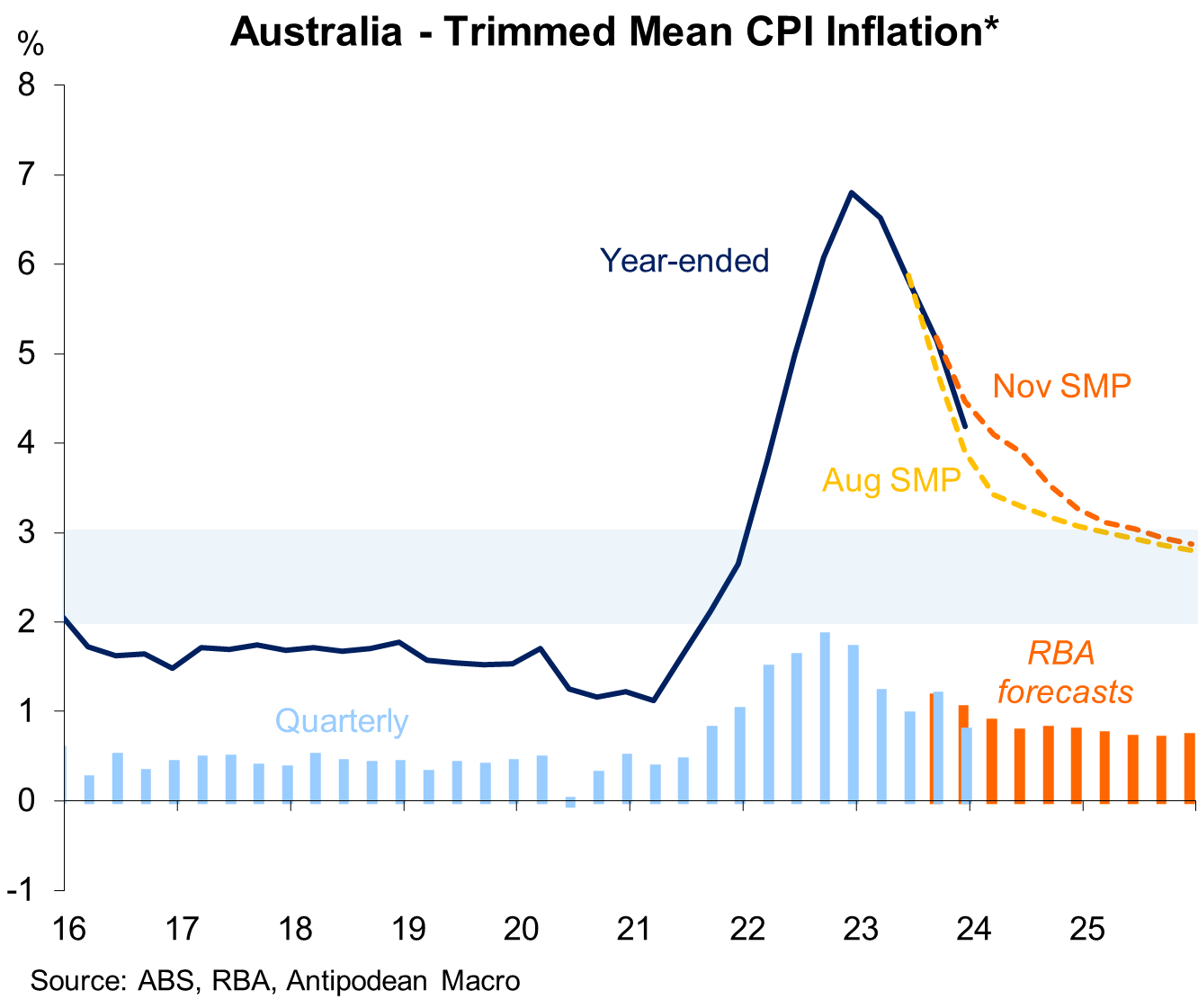

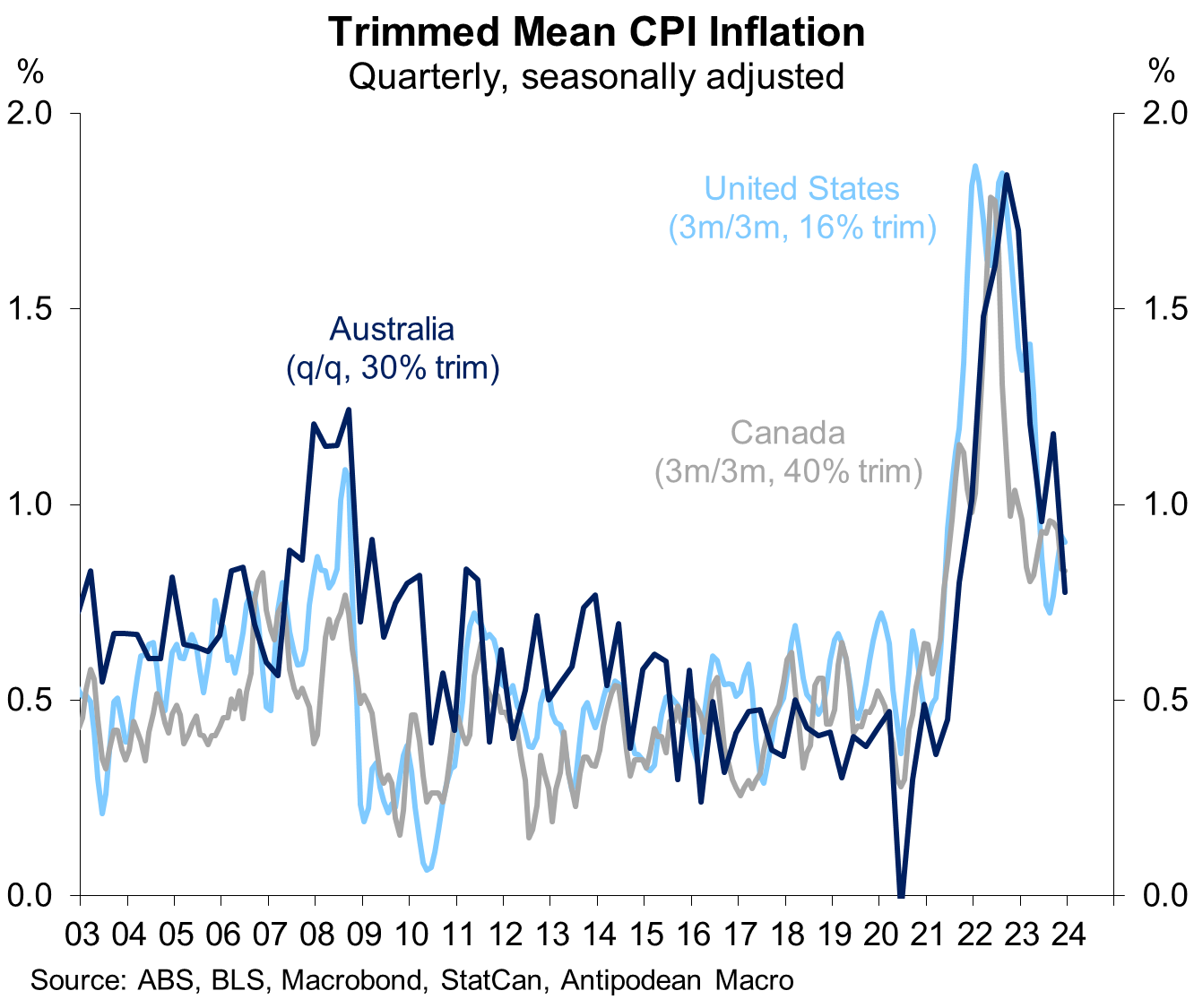

Measures of underlying inflation also moderated in Q4. The RBA’s preferred trimmed mean measure slowed to 0.8% q/q as we expected (vs market expectations for +0.9% q/q).

While the Bank would have had more accurate up-to-date internal nowcasts, the outcome for trimmed mean inflation was 0.2ppts below the latest public forecast in the November Statement on Monetary Policy.

The speed and size of the decline in trimmed mean inflation in Australia is now broadly similar to the experience in the US and Canada.

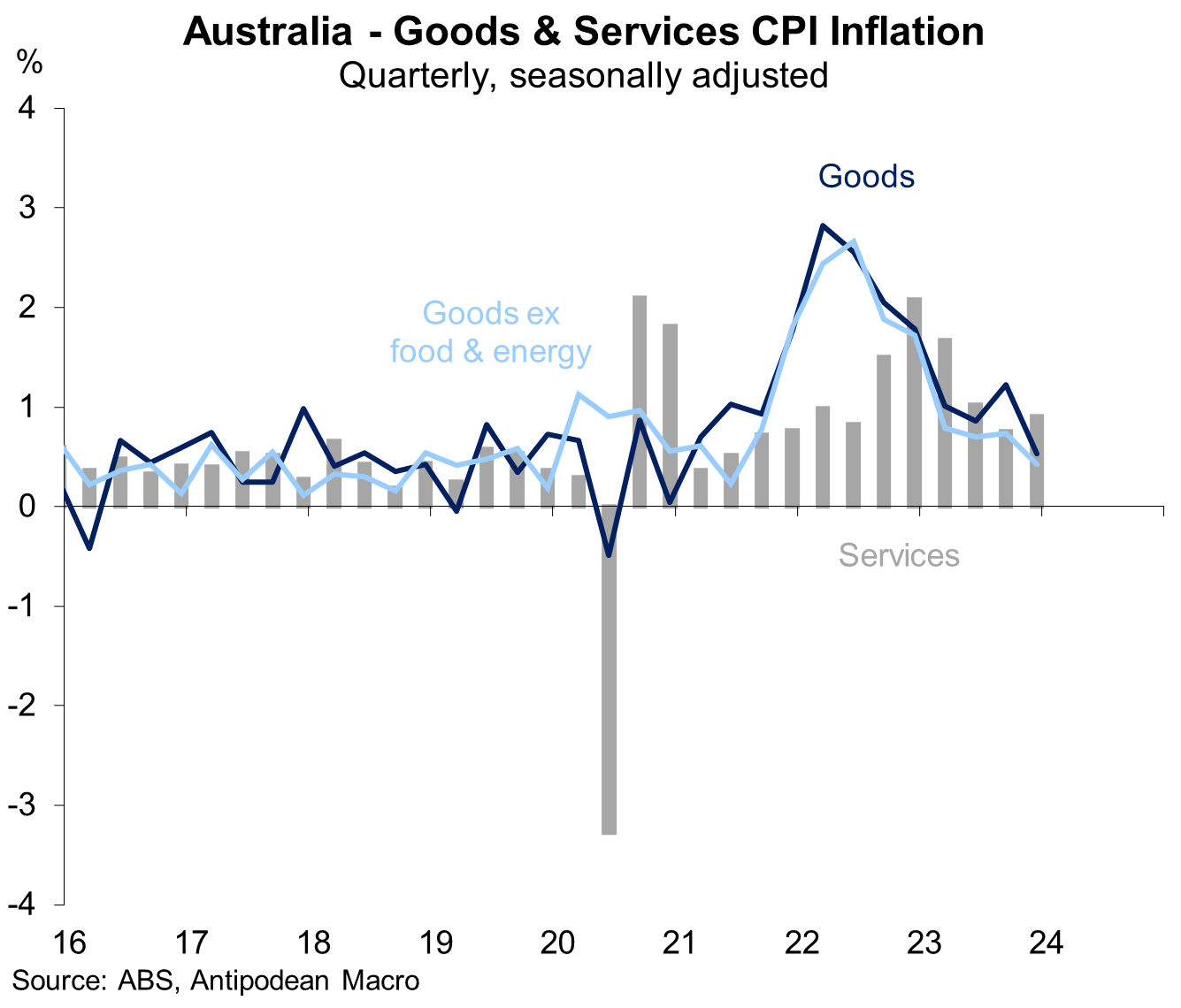

Sticky, but lower, ‘domestic’ inflation offset by imported deflation

As foreshadowed in our CPI preview, Australia’s CPI inflation towards the end of 2023 was characterised by sticky ‘domestic’ inflation but falling tradables prices.

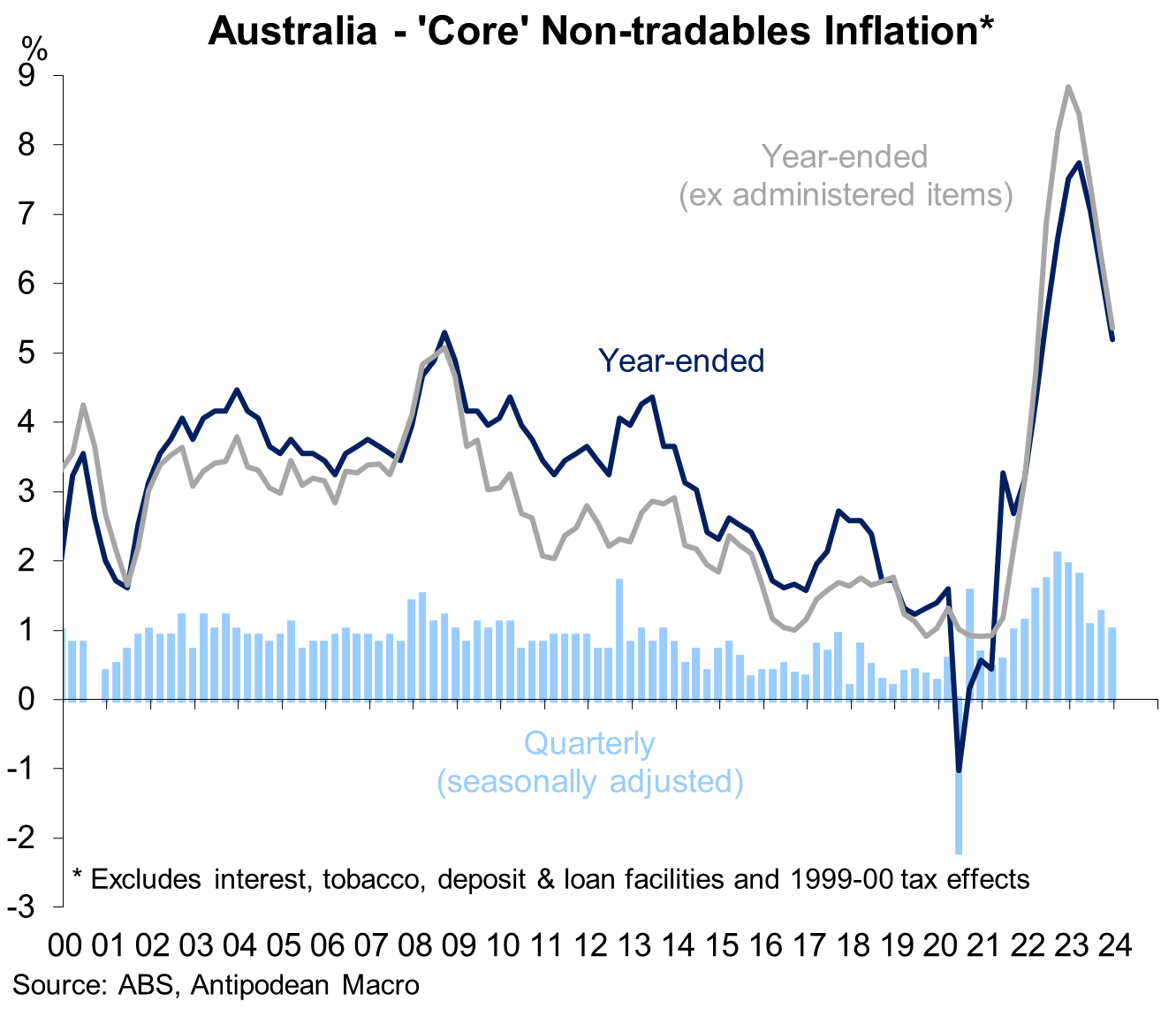

Non-tradables inflation of +1¼% q/q (seasonally adjusted) was very close to our expectation.

In part this reflected sharp increases in tobacco prices (+7% q/q) in October/November following the government’s 5% excise increase in addition to the usual semi-annual indexation process (to wages growth).

Excluding tobacco, ‘core’ non-tradables inflation moderated a little to +1% q/q (seasonally adjusted) as we expected. This is well down from the 2%-plus quarterly peak in 2022 and only a little above the +0.9% quarterly average over the 2000-13 period (and before the RBA target undershoot from 2014-19).

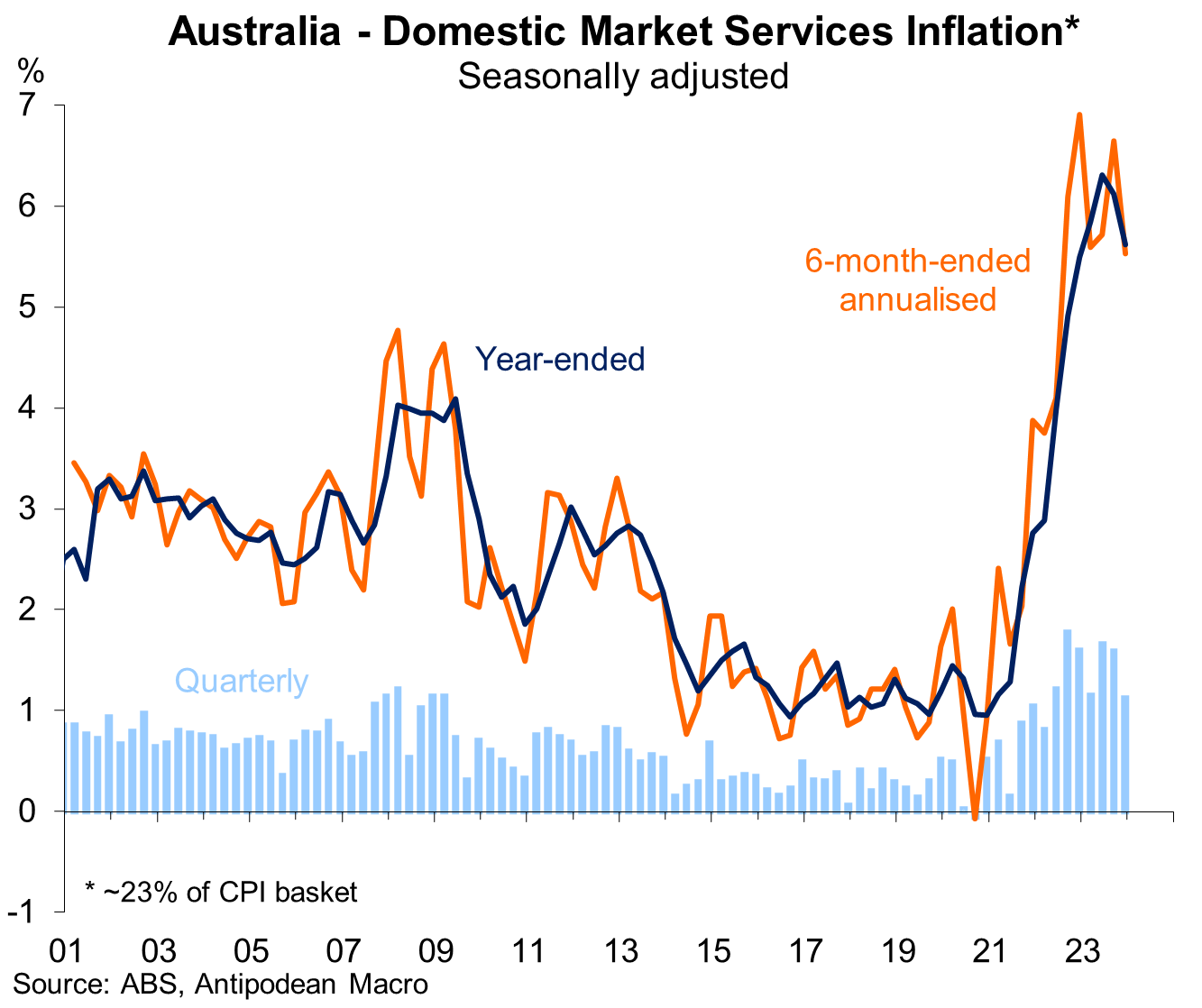

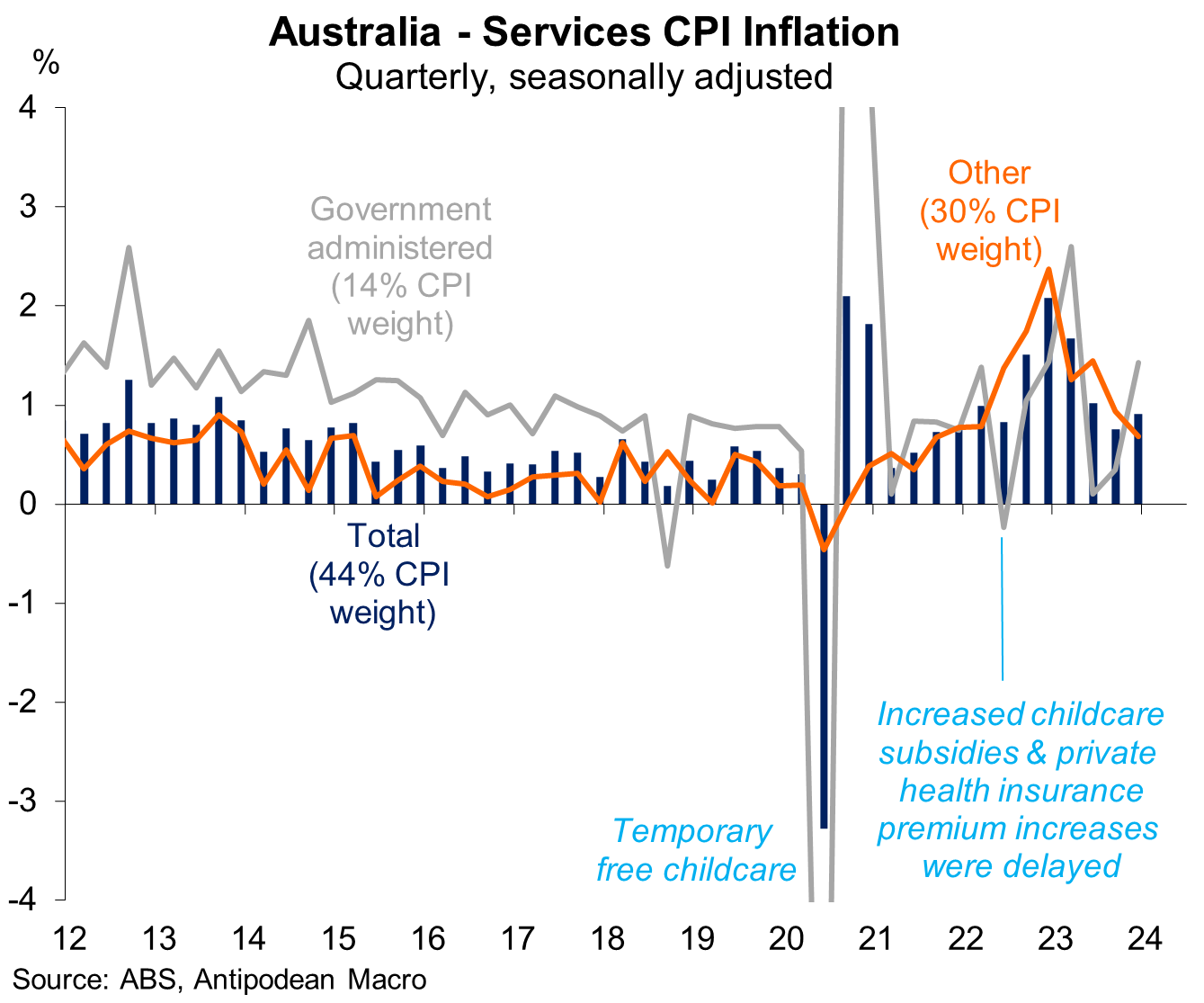

Within non-tradables inflation, domestic market services inflation - nearly one-quarter of the CPI basket - moderated in Q4 to 1.1% q/q (again, in line with our forecast).

In part this reflects lower price increases for meals out & takeaway (+0.9% q/q) compared with the prior two quarters. In contrast, price rises for insurance remained very strong in Q4 (+3.5% q/q, seasonally adjusted).

Government-administered (excl. tobacco) inflation was a solid +1.3% q/q (seasonally adjusted) in Q4. Government electricity price subsidies introduced in July and typically paid quarterly continue to dampen prices paid by a significant share of households.

Together, administered price categories and tobacco contributed around half of the increase in the seasonally adjusted CPI in Q4.

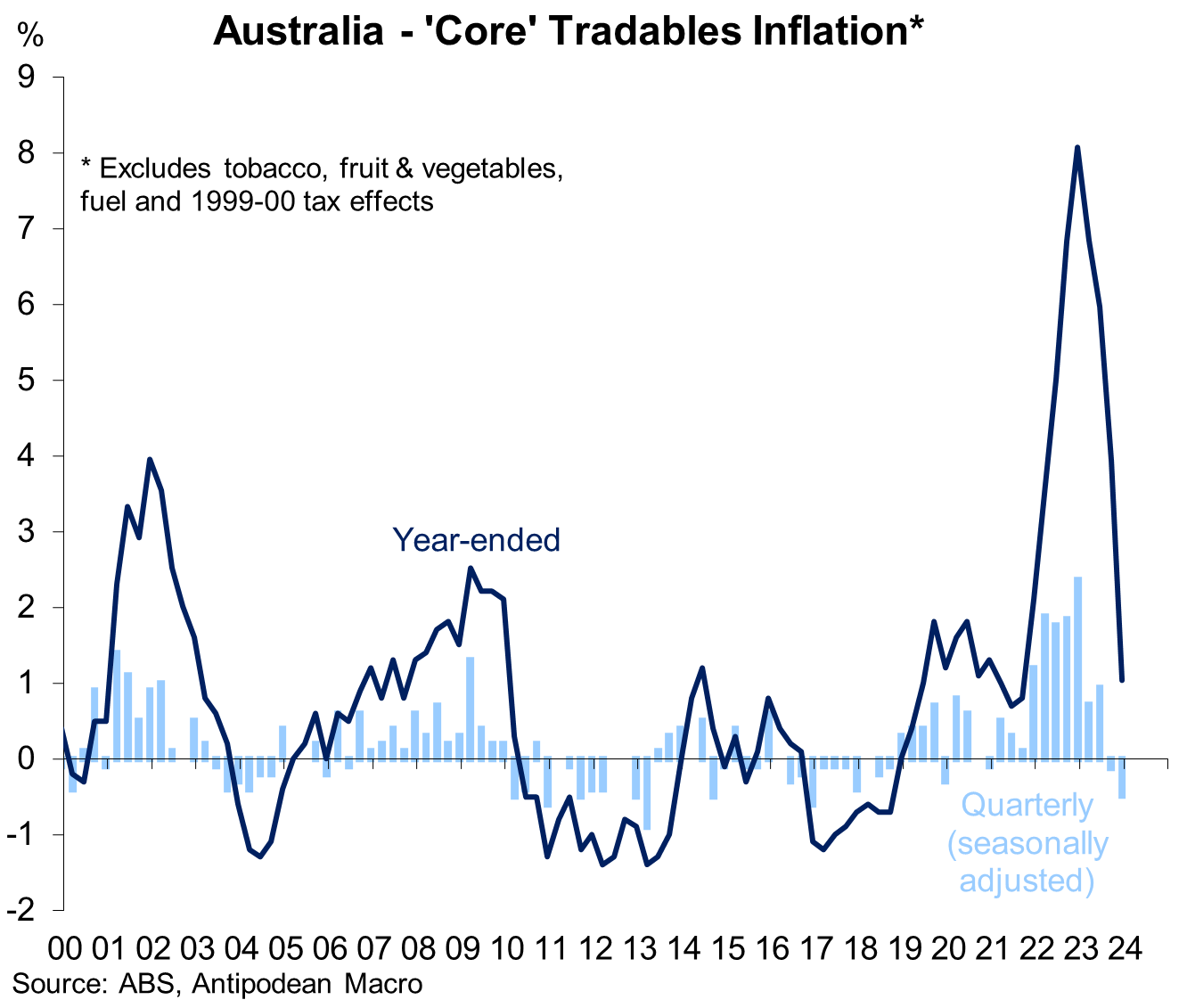

Tradable CPI categories collectively fell in price in Q4. Excluding ‘volatile’ items (fuel and fruit & vegetables), ‘core’ tradables prices declined by 0.5% q/q in the quarter (in line with our nowcast). Fuel prices declined slightly (-0.2% q/q).

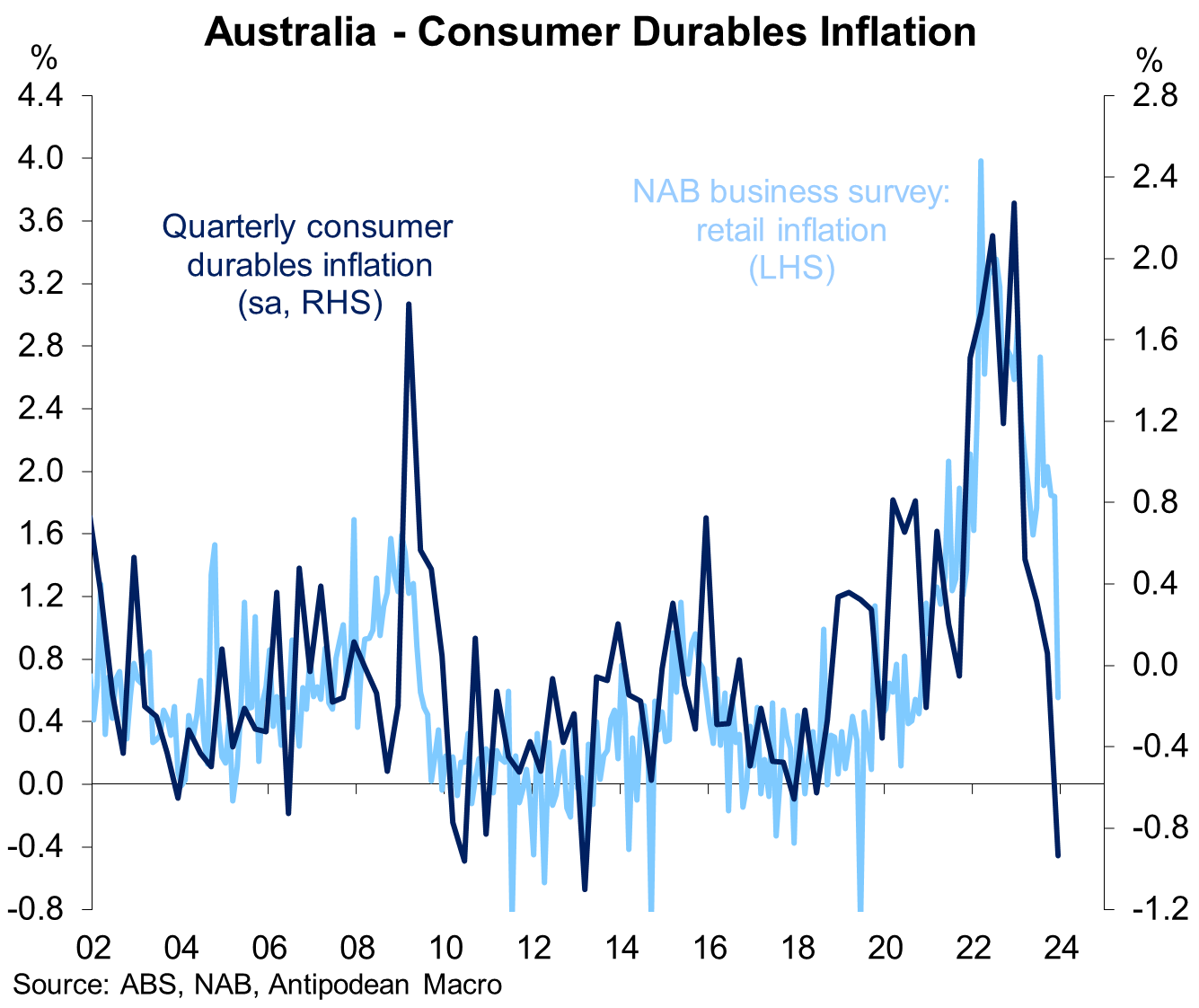

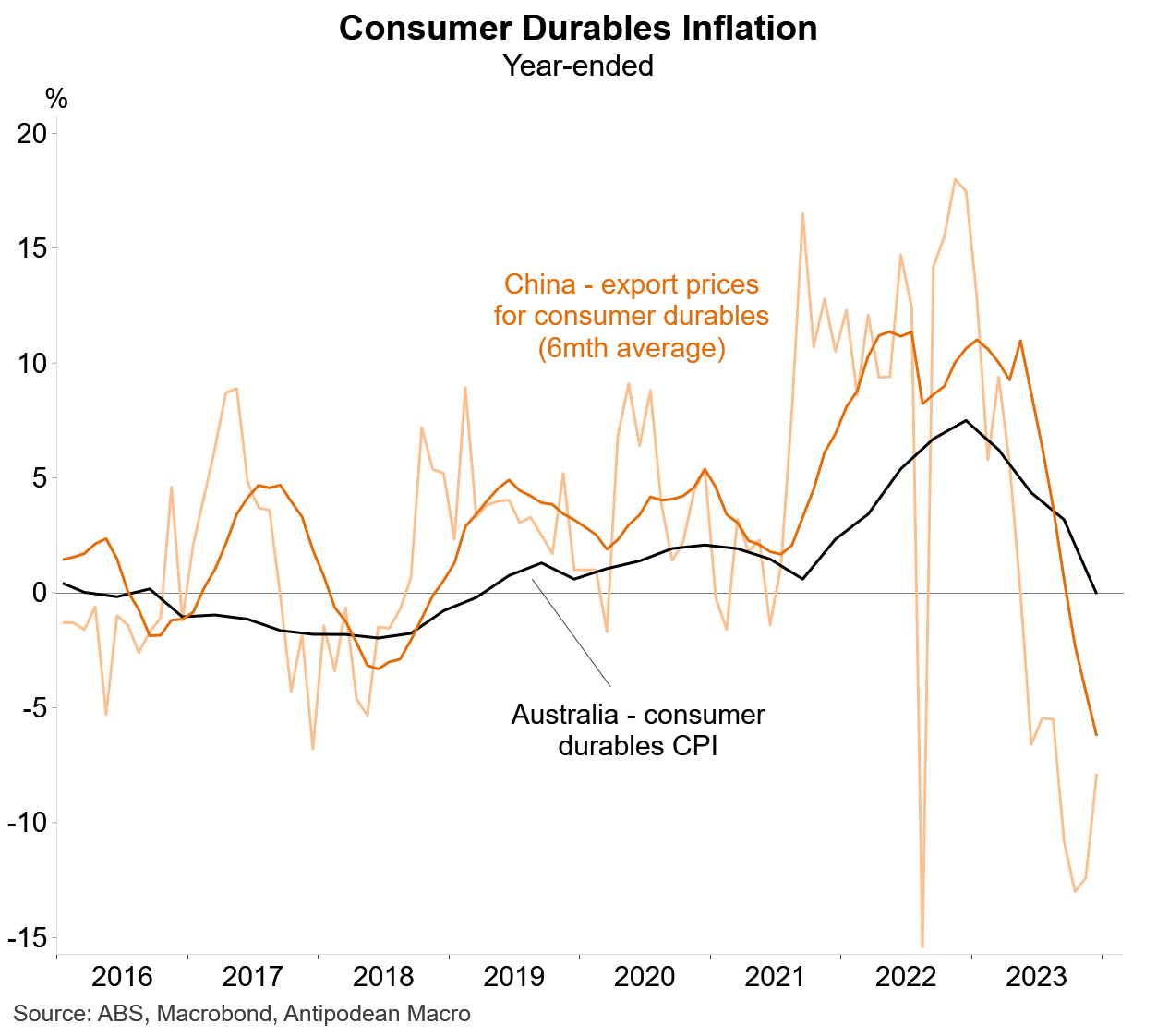

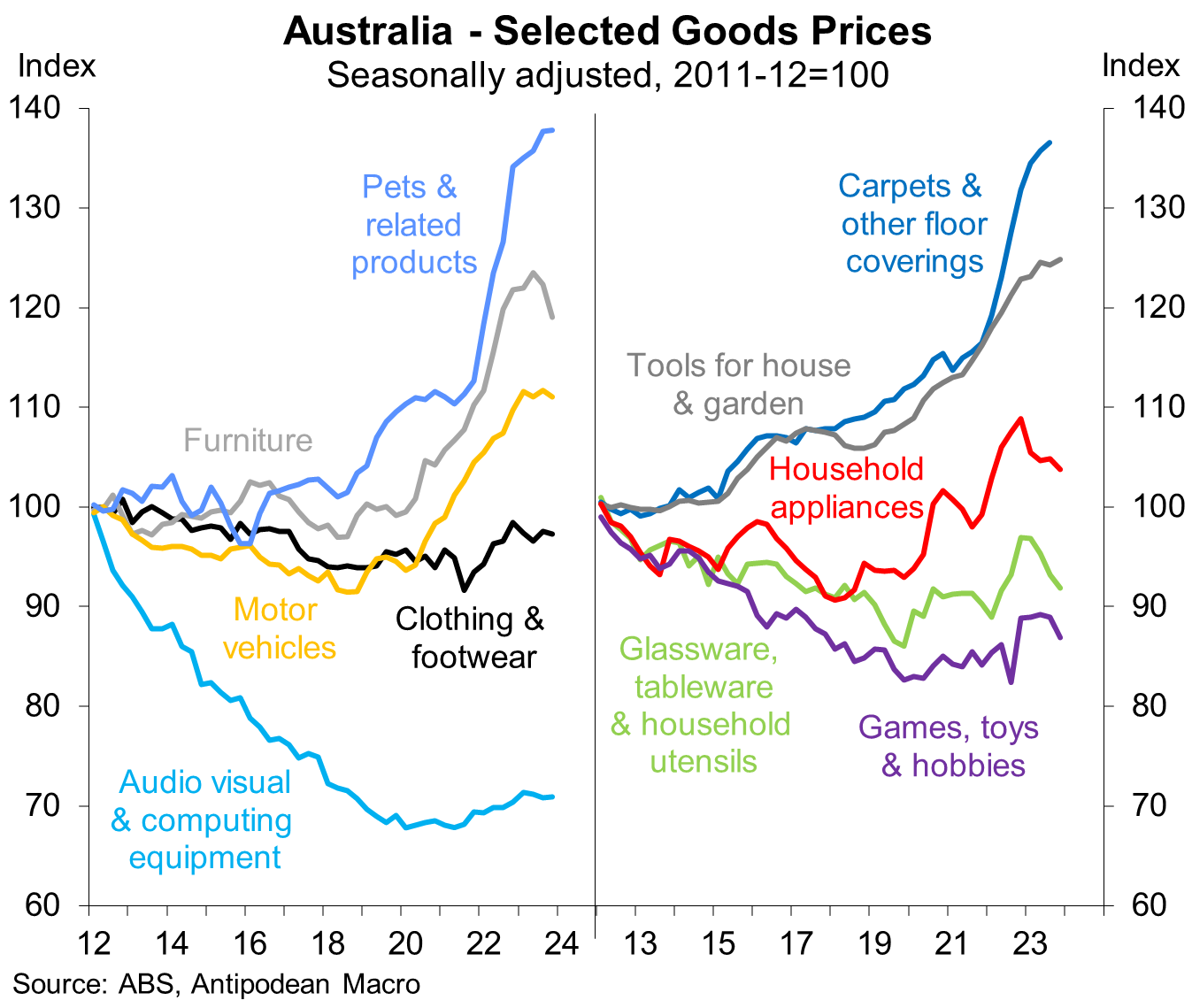

Prices for consumer durables, which account for nearly half of the tradables CPI, declined sharply in Q4. Price falls were most pronounced for household goods. This is consistent with weaker import price inflation (including from China), lower freight costs and soft goods demand.

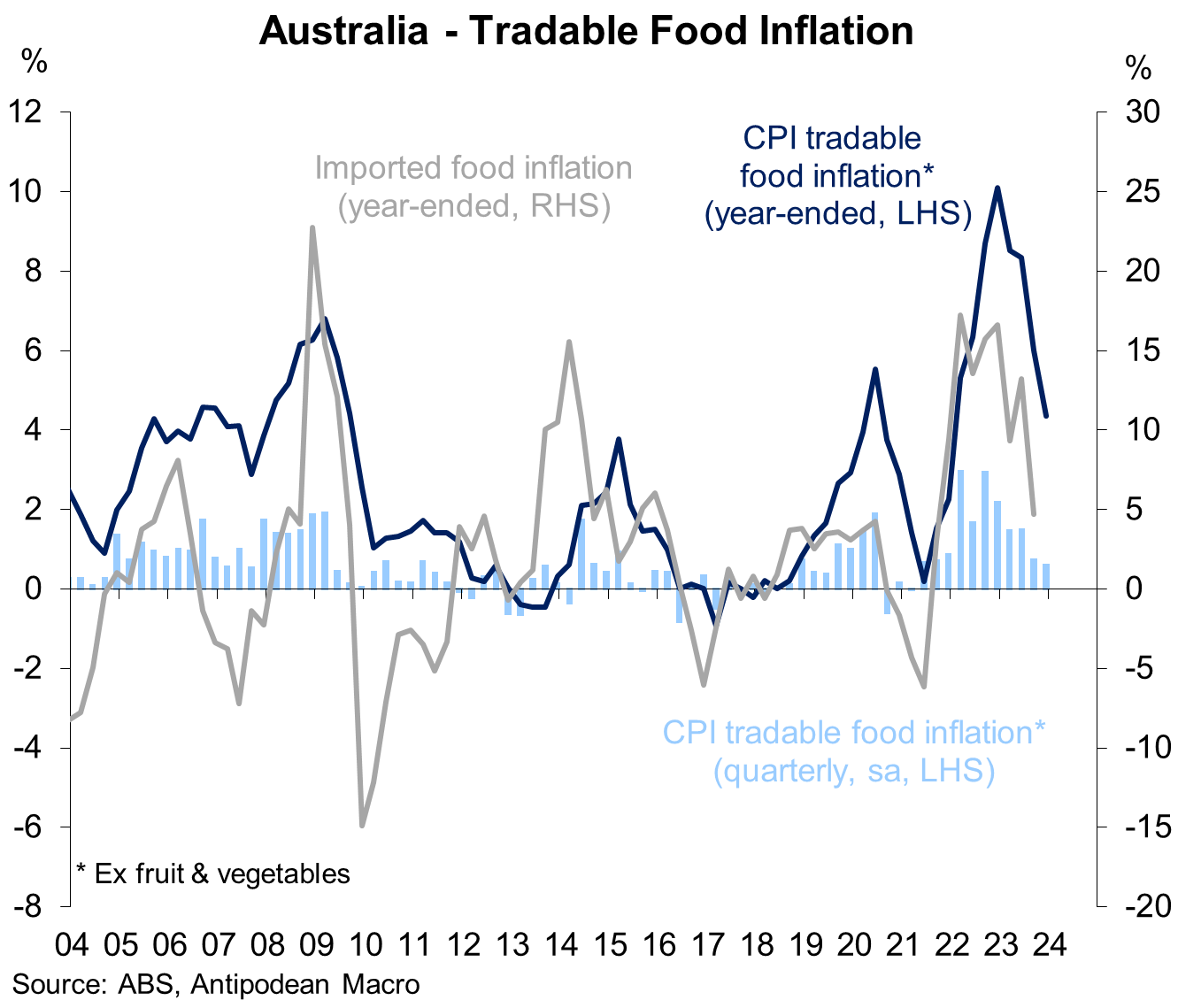

Tradable food inflation has also moderated significantly amid slowing imported food inflation.

The weakness in tradables and consumer durables inflation was reflected in lower goods inflation overall in Q4.

Underlying housing inflation remains strong

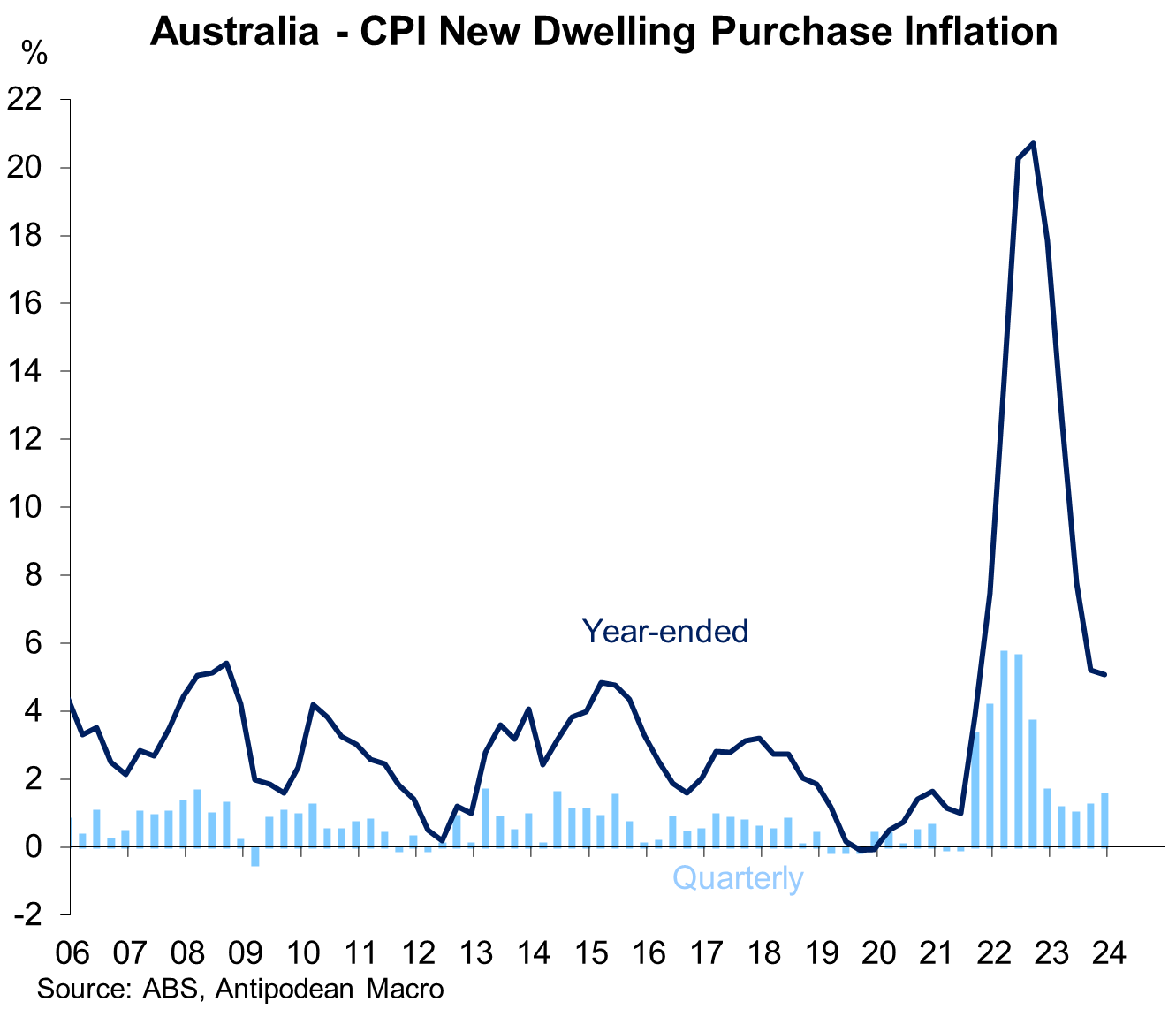

Goods inflation in Australia includes new dwelling purchase by owner-occupiers as this reflects the cost to build new homes (imputed owner’s equivalent rent is captured as a service in the US and other economies). This increased over H2 2023 and remained fairly solid.

Anecdotal evidence of strong price rises for some residential construction inputs from February suggest that new dwelling purchase inflation is unlikely to moderate further in the near-term.

Despite weak demand for new housing, it is possible that the resurgence in established home prices last year emboldened developers to lift new home prices a little faster (and/or reduce incentives).

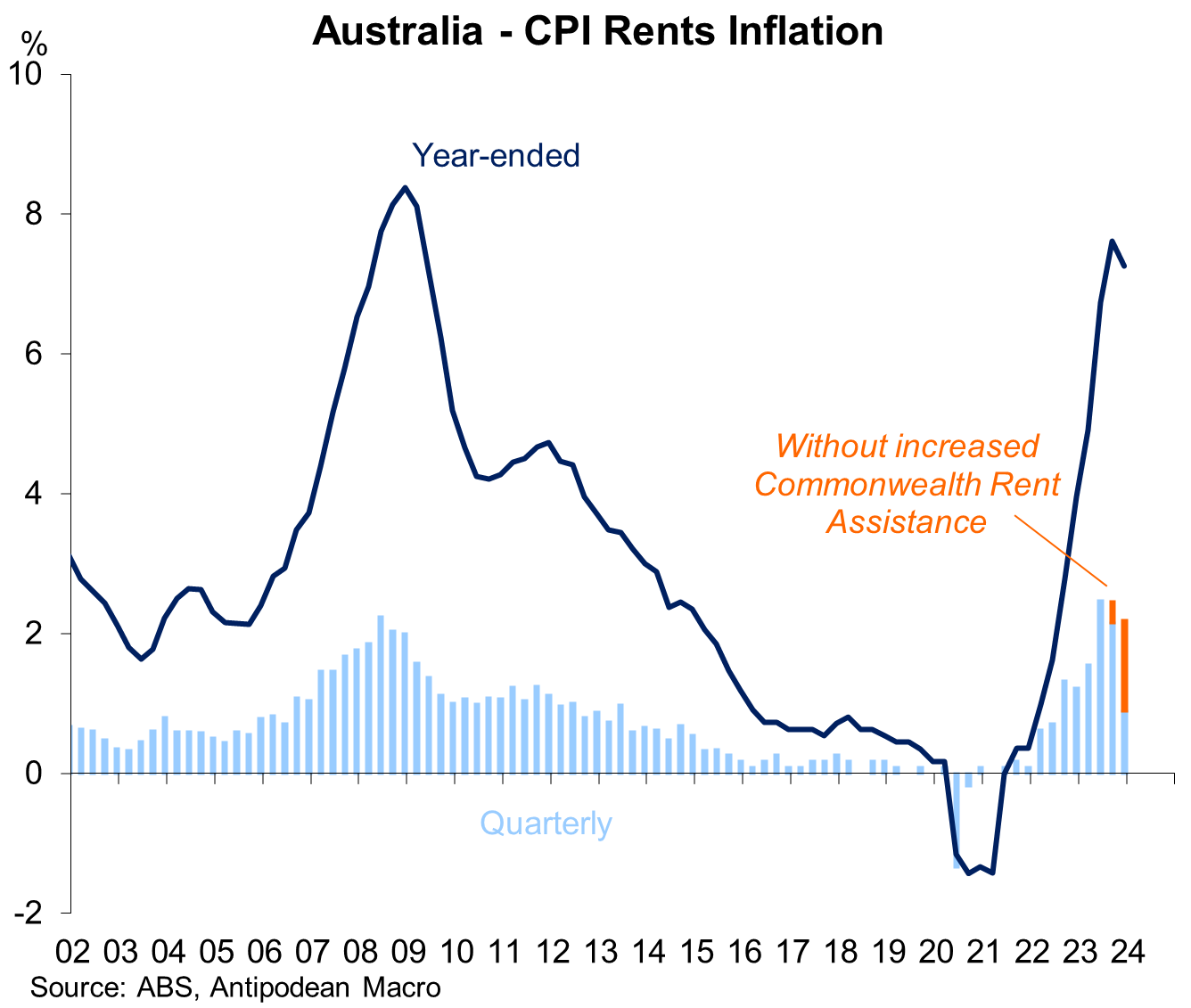

CPI rents inflation moderated in Q4 (+0.9% q/q) as the Government’s additional 15% increase to Commonwealth Rent Assistance for 1.1m households from 20 September - which is treated as a subsidy in the CPI - partly offset strong underlying rent increases.

Rents would have risen 2.2% q/q without the increase to rent assistance, which would have resulted in Q4 headline and trimmed mean CPI inflation being almost 0.1ppts higher than publishes.

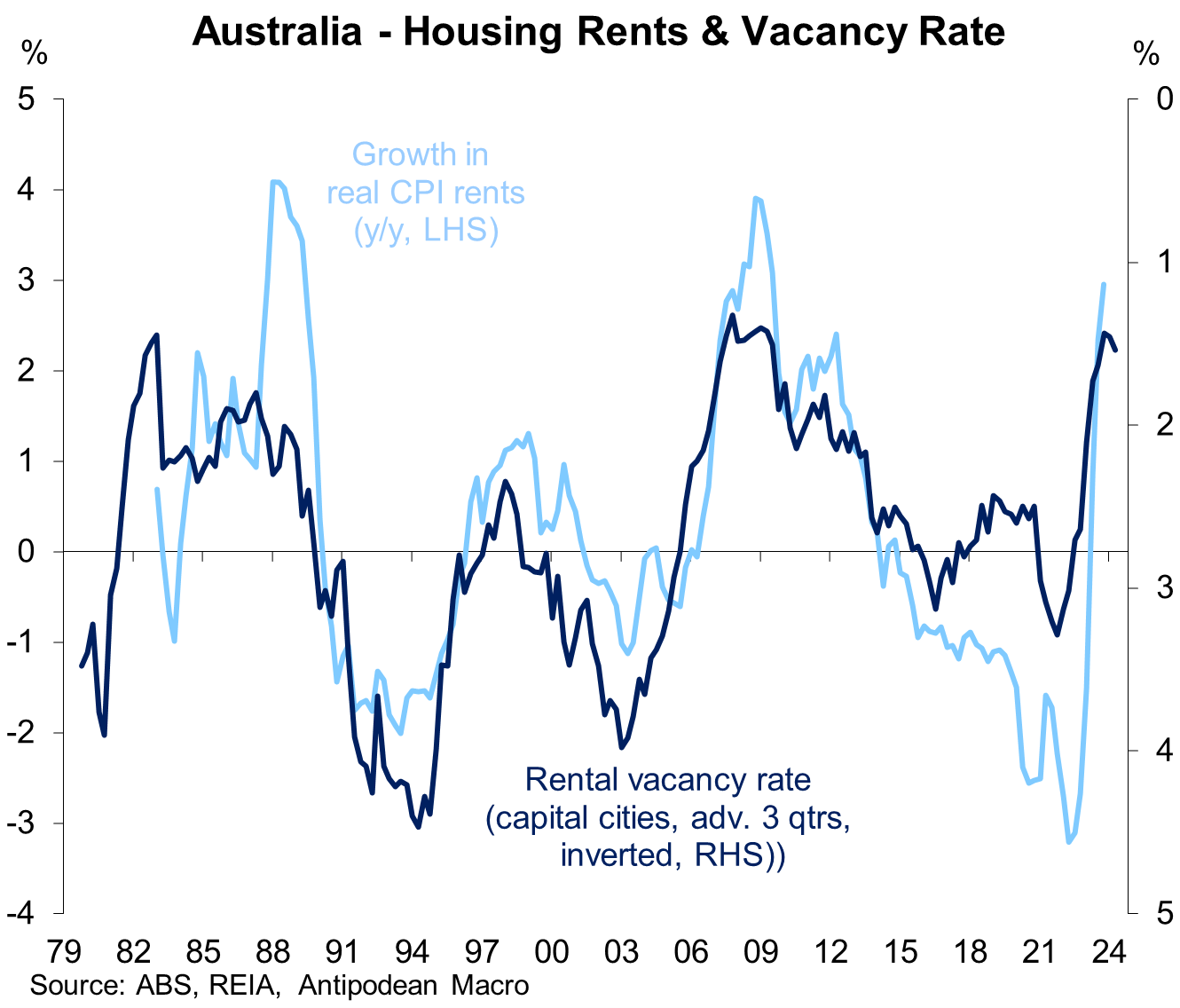

Rents inflation is also likely to remain strong amid very low rental vacancy rates and as fast growth in new rental agreements feeds through gradually to the CPI (stock) measure.

Services inflation to remain elevated

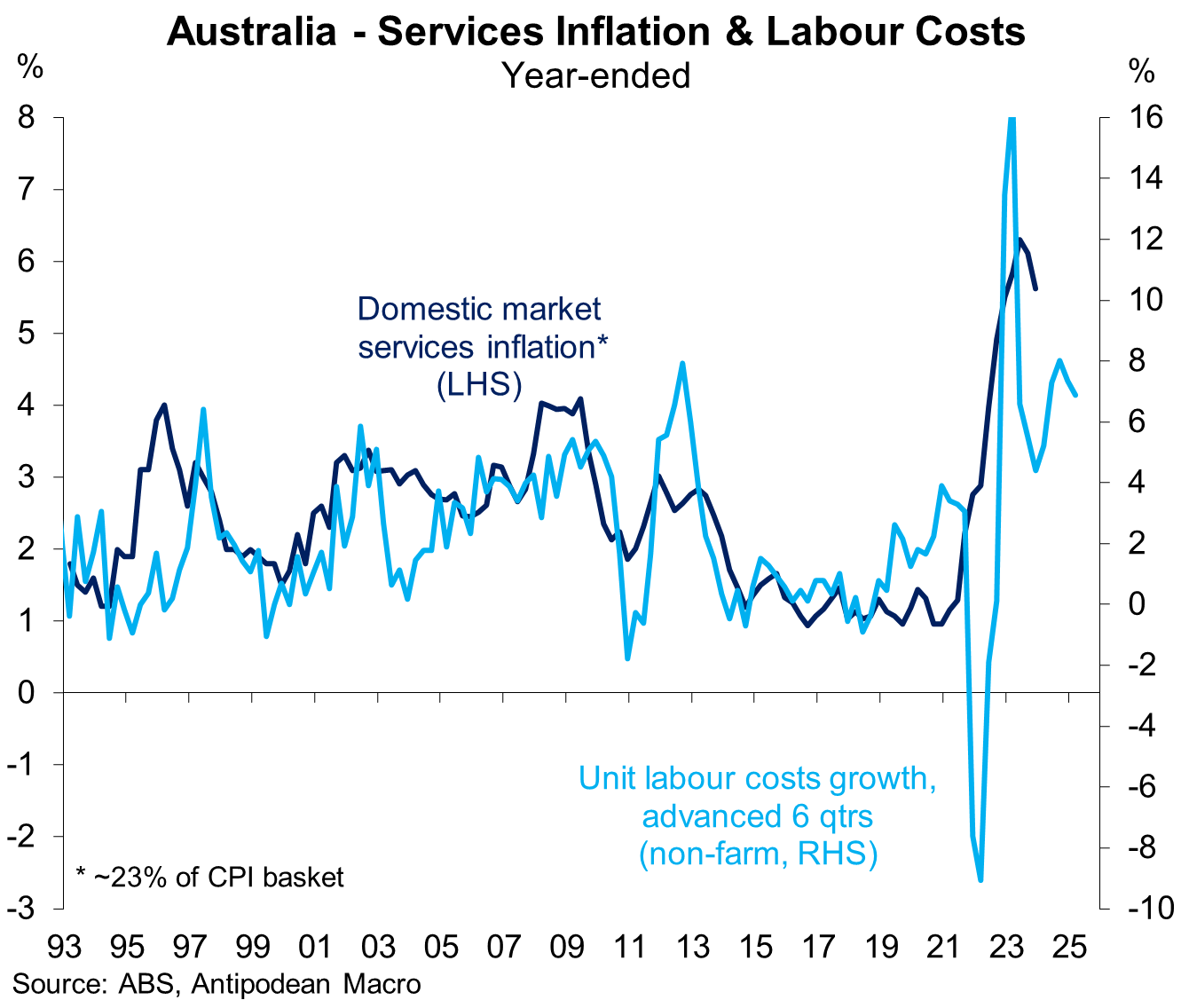

Absent an abrupt adverse economic shock, services inflation in Australia is likely to remain at slightly uncomfortable levels (for the RBA) for a little longer and until significant progress is made on lowering growth in unit labour costs. This is likely to require slower growth in employment and/or wages growth.

Encouragingly, signs of less-stretched capacity in the Australian economy should, with a lag, flow through to slower growth in unit labour costs and services inflation.

Interestingly, all of the modest uptick in total services CPI inflation in Q4 was because of a sharp increase in administered services inflation (child care; delayed increases to private health insurance premiums; postal services; and urban transport fares).

More market-determined services prices showed further disinflation in aggregate.