Aussie population growth to slow, a lot

Australia’s net immigration will slow as:

the post-COVID surge in arrivals, particularly students, settles down;

departures from Australia normalise from a low level; and

finding work becomes more challenging amid less favourable labour market conditions.

It won’t be too long before population growth is more of an after thought for the RBA.

A recap on recent population growth

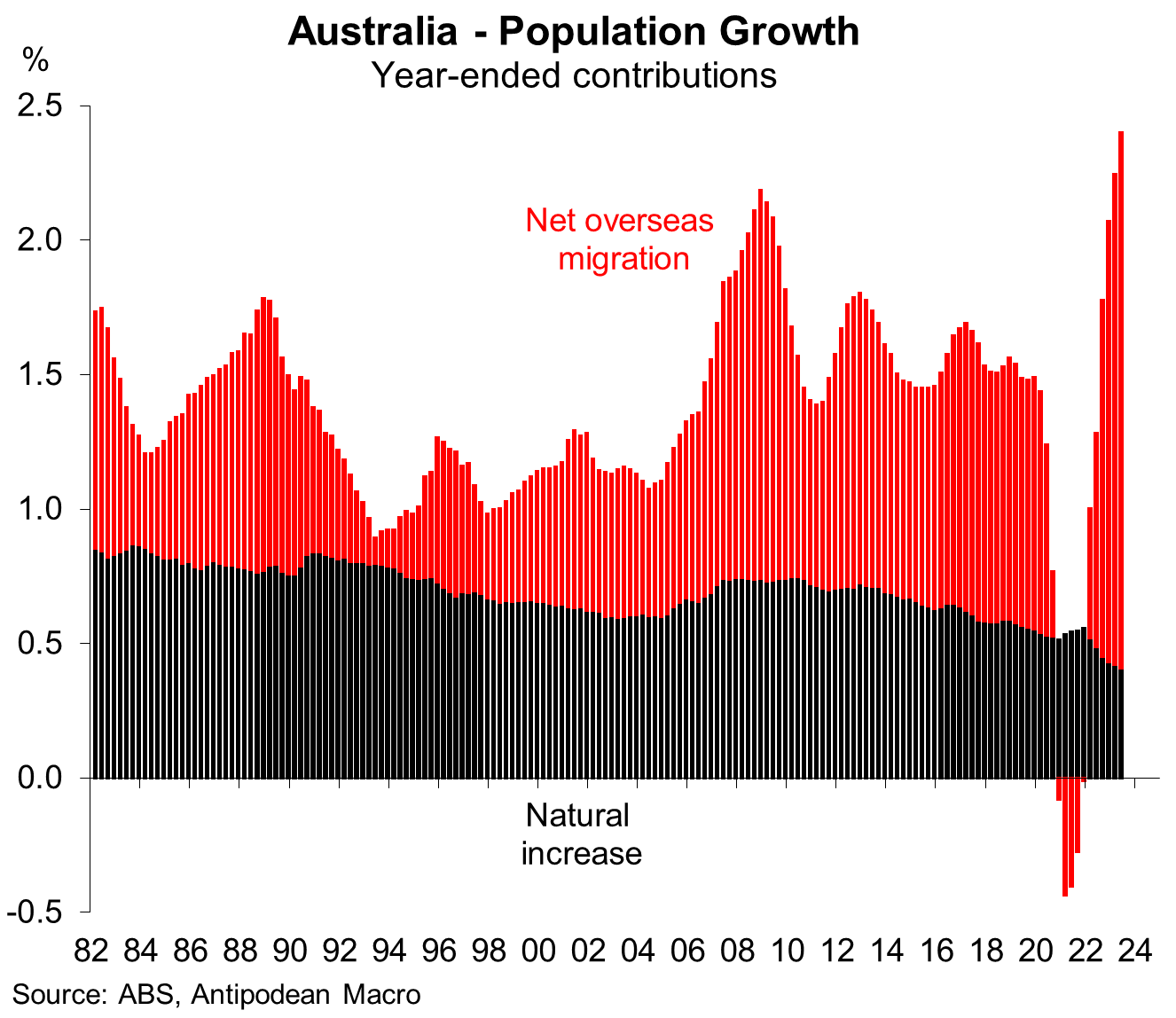

From 1971 until the pandemic, Australia’s population growth averaged 1.4% per annum. Over the period from 2011 and 2019, annual population growth averaged 1.6% but had slowed a touch to 1.5% in the year before the pandemic.

As COVID struck, there was a temporary net outflow of people from Australia, and the population barely grew for a short period.

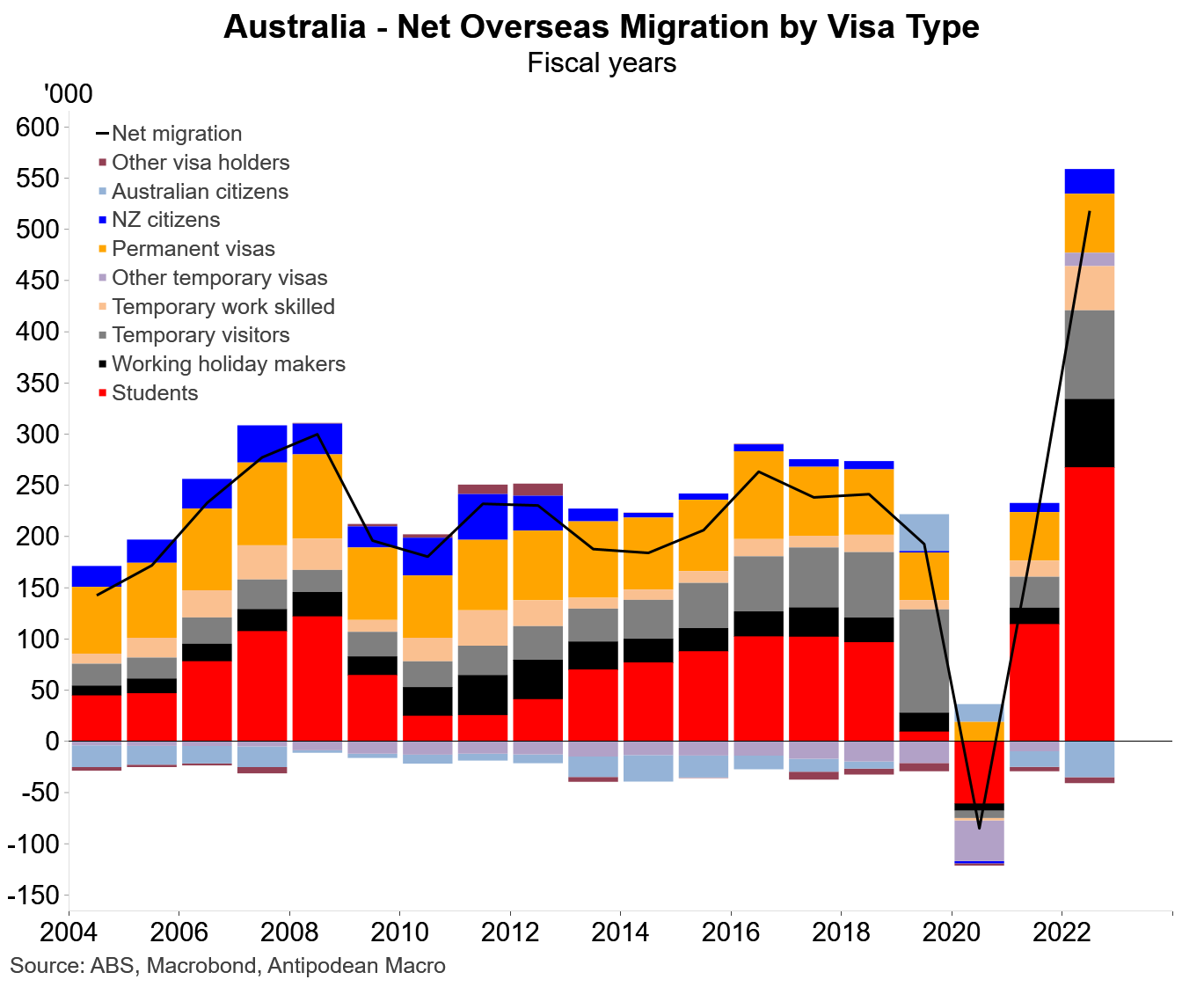

Net immigration has since rebounded sharply, with preliminary figures putting it at 518,000 persons in the year to 30 June 2023. This contributed 2ppts to overall population growth of 2.4% (or 624,000 persons) over that period (with the contribution from natural increase continuing to trend lower).

A sharp bounce-back in population growth has also occurred in other “high immigration” countries (Canada and New Zealand).

The rapid increase in Australia’s net immigration reflects both that arrivals have risen above pre-COVID levels and departures from Australia have remained relatively low.

Despite hyperventilating in some quarters about the recent sharp increase in net immigration, Australia’s population in real time is only likely to be approaching the pre-COVID trend (estimates for the period since the June quarter use information from the labour force survey).

Similarly, the number of temporary visa holders in Australia has just roughly returned to the pre-COVID trend. Temporary visa holders, particularly international students, accounted for the majority of the increase in net immigration in 2022-23.

(People arriving to Australia are included in the resident population if they are, or expected to be, in Australia for at least 12 months of a 16-month period.)

While the surge in net immigration has so far largely been ‘catch-up’ to the pre-COVID trend in the level of the population, this is not to say that it hasn’t been disruptive to some parts of the economy. It has, including for the housing market where the initial plunge in immigration is likely to have contributed to some plans for higher-density housing to be delayed or pulled.

It’s another example, however, of how disruptive the pandemic has been to economies, and how persistent some of those disruptions continue to be.

Strong immigration has recently supported demand growth

Permanent and temporary migrants contribute to the economy. While the debate will rage about the relative strengths of the short-run supply-and demand-side effects of immigration, it is clear that the rebound in net immigration has supported demand.

The problem is that it is difficult to isolate the demand effects of migrants.

Why? Estimates of household consumption include spending by migrants - except international students - captured in the resident population. Spending by international students - no matter how long they are in Australia - is recorded as education exports.

To that end, overall growth in spending by residents in Australia (grey bars in chart below) has been very weak.

Aggregate consumer demand growth, however, has been supported by spending in Australia by international students (of which a high proportion stay in Australia for longer than one year). More than half of the spending by international students in Australia is on goods and services other than tuition fees.

Net immigration will pull back…

It’s not a big call to say net immigration will slow.

Treasury’s latest forecasts (in the recent MYEFO) anticipate a decline in net immigration from more than +500k in 2022-23 to +375k in 2023-24 and +250k in 2024-25.

This would entail a slowing in annual population growth to 1.3% within two years. That’s probably a reasonable guesstimate, though Treasury’s forecasts have significantly missed the mark in recent years.

Monthly data on movements across Australia’s borders by visa type - which are a rough proxy for net immigration excluding Australian citizens - suggest that net immigration could already be starting to slow.

As noted above, longer-term departures from Australia have remained well below pre-COVID levels. The decline in departures of student visa holders vis-a-vis pre-COVID levels accounted for a large share of the total fall in departures from Australia.

But this will change, including as departures of international students return to more normal levels with a lag to student arrival numbers.

…including because labour market conditions won’t be as favourable

Australia’s net immigration has typically fluctuated (with a lag) with labour market conditions. This shouldn’t be overly surprising given Australia’s relative remoteness and peoples’ ‘home bias’ tendencies during worsening economic conditions.

As a result, expectations for rising unemployment are likely to contribute to slower net immigration.

Great piece! Do you have any strong opinions on what the *right* level of overseas migration is? It sounds like you're saying it's going to return to roughly pre-COVID levels (of say, 250,000) - but was that a good amount? i.e. are you aware of any good thinking / research on where that sweet spot is between supporting demand / supplementing the birth rate vs impacts to housing / labour market etc